There is a wealth of information available at Postflopizer that can take your game to the next level. Being able to study a hand you played, with Postflopizer as your coach, will reap dividends if you make it a habit.

But if you are new to this technology, it can be overwhelming at first. Knowing what to work on and which metrics matter is a skill in itself.

In this article, I am going to show you what some of the most important questions you should be asking yourself are in a post flop hand review, then show you how you can arrive at meaningful answers using Postflopizer GTO Solver. These questions will not only be useful in the hand review, they will cultivate the same habit of asking them when you are playing a hand at the tables.

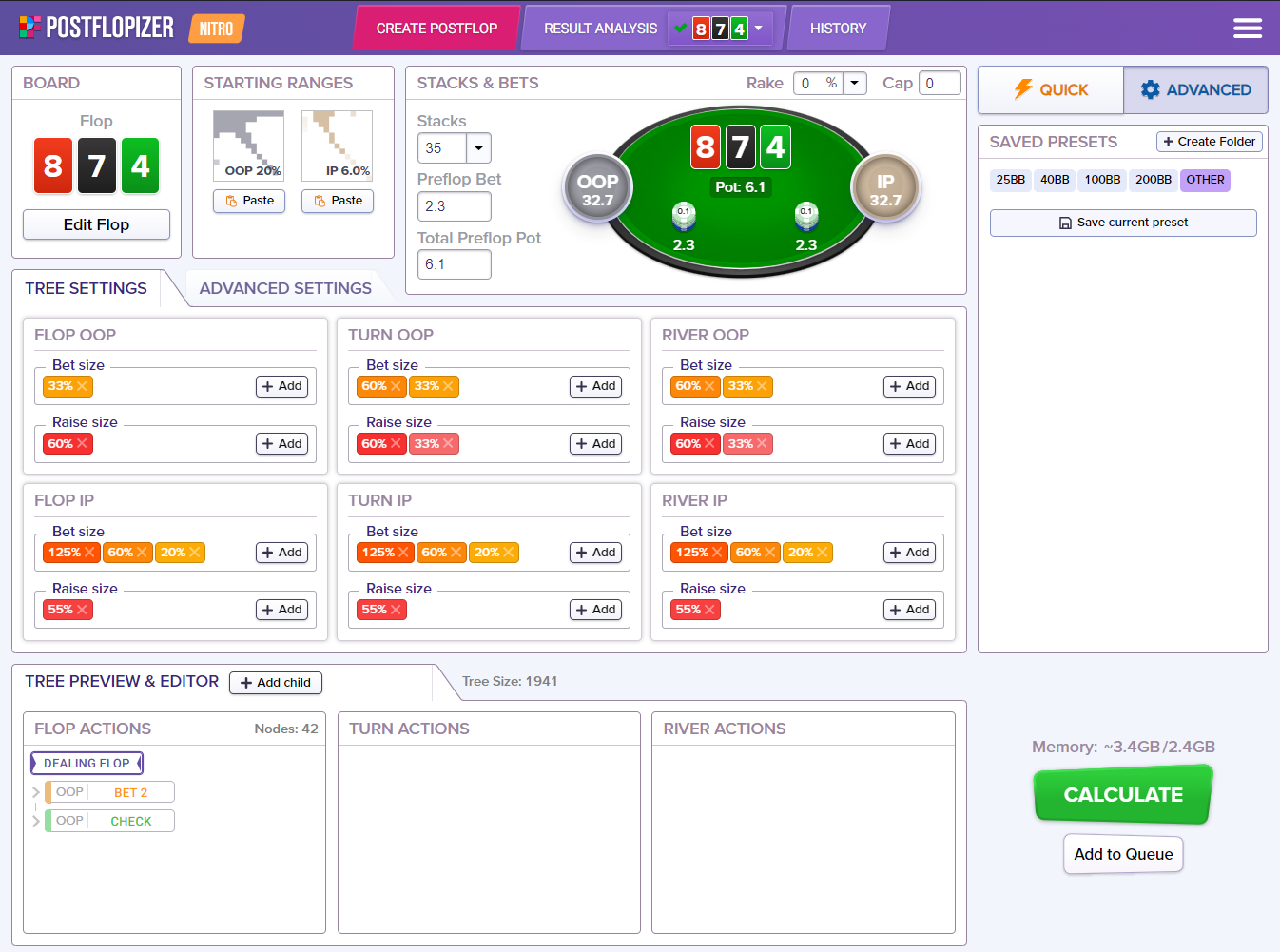

First things first, this article assumes you know the basics of how to set up a hand using Postflopizer. It also assumes that the hand ranges and bet sizes you have input reflect the actual ranges and sizes your opponents use in-game. These are the only two inputs where you have to bring something to the table, Postflopizer can do the rest. If in doubt, use GTO-approved preflop ranges and make sure you at least have a small and a large bet sizing on every street, then as you get used to studying hands try to get the ranges and bet sizes as close to accurate as possible.

These are some great starter questions to ask yourself in any hand review, which will see you become a better player if you ask them. They are roughly in the order you should ask them when reviewing a hand:

What are the shapes of the preflop ranges?

You already know this because you input the ranges yourself, but now is a time to dig deeper.

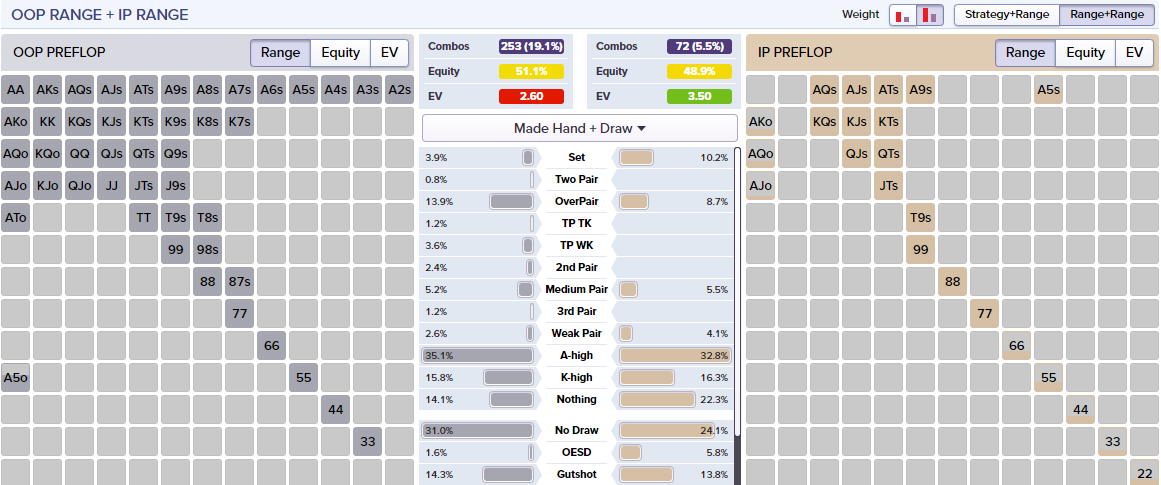

Postflopizer allows you to look at ranges side-by-side for easy comparison. The first thing to look at is the shape of each range, to determine who is likely to be ahead.

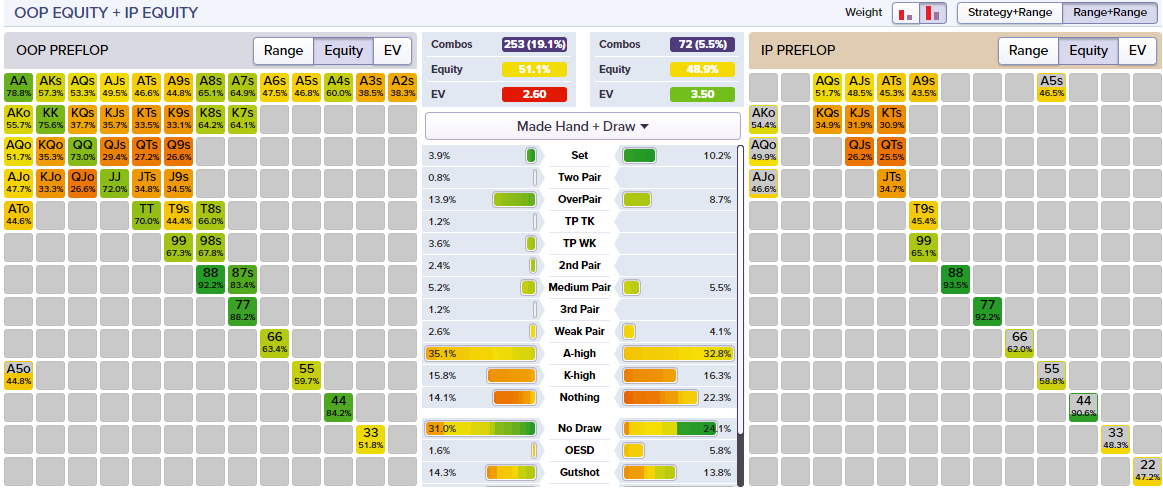

In this example we are 35BBs effective, UTG (OOP) vs UTG1 (IP) Single Raise Pot, the flop is 8♥7♠4♣ (rainbow).

Before we look at this flop specifically, let’s quickly look at the preflop ranges. OOP has a tight linear range (ie. all the best hands). Linear ranges tend to dominate most flops, especially Ace high and paired flops. They tend to bet often, usually for a small sizing.

IP has a tight condensed range (mostly medium-strength hands). Condensed ranges usually perform well on Broadway or Middle-card centric flops, but often have to play cautiously.

Other types of preflop ranges

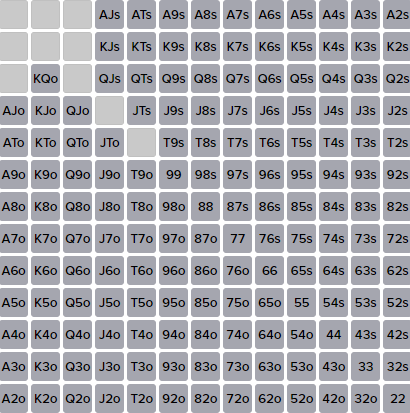

This is unrelated to the hand we are reviewing but the other two range types are capped ranges, which look like this:

Capped ranges tend to have medium strength and weak hands, but no strong hands in them. They tend to perform well on low-connected flops but otherwise typically play a passive bluff-catching style.

There are also polarised ranges:

Polarised ranges

Polarised ranges tend to have very strong hands and weak hands as bluffs, with nothing in the middle. Polarised ranges tend to play aggressively and bet for larger sizes.

Back to our 874r flop

Back to our 874r flop, we would expect OOP to have an advantage because they have more overpairs. We can answer whether this is the case by looking at the equities of both ranges:

This is one of the most important outputs in Postflopizer. We can see that OOP has a slight overall advantage of 51.1%. However, it’s more useful to look at where that advantage lies by looking at the colour coding on both grids. Green means strong, yellow means OK, and Orange means weak hands. We can see a strong green diagonal line on OOP’s grid, signalling most of their equity is coming from pocket pairs, both the Sets and the Overpairs. The green for IP is mostly just the Sets.

Looking between the two grids we can see how big a percentage of the overall range each hand class is. Sets are 10.2% of the IP range, they are 3.9% of OOP’s range. Overpairs are 13.9% of OOP’s range, they are 8.7% of IP’s range.

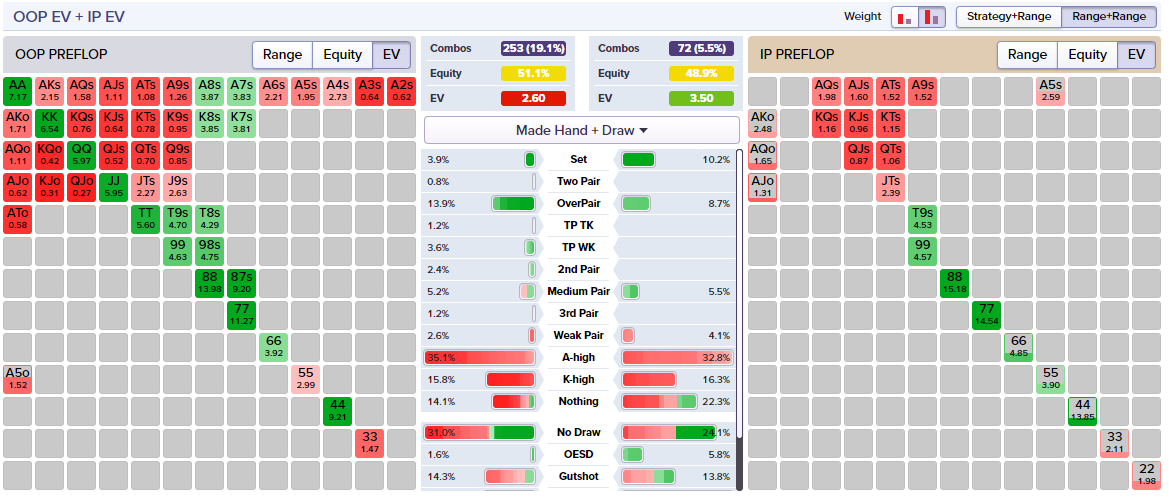

It’s also useful to look at the EV’s of both players:

IP has an EV of 3.5BBs while OOP has an EV of 2.6BBs. Despite having a slight equity advantage, OOP makes less on average in this hand. This is because, as their name suggests, OOP is out of position. The equities are close, but OOP will be at an informational disadvantage throughout the hand.

We know that OOP has a stronger range with more overpairs, but it is close, and the IP player’s positional advantage counts for a lot.

What does my range do?

It’s understandable that you would want to see what your hand does from the session you just played, but a more useful question is to ask what your whole range does.

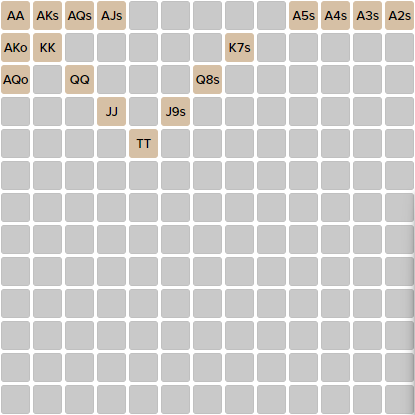

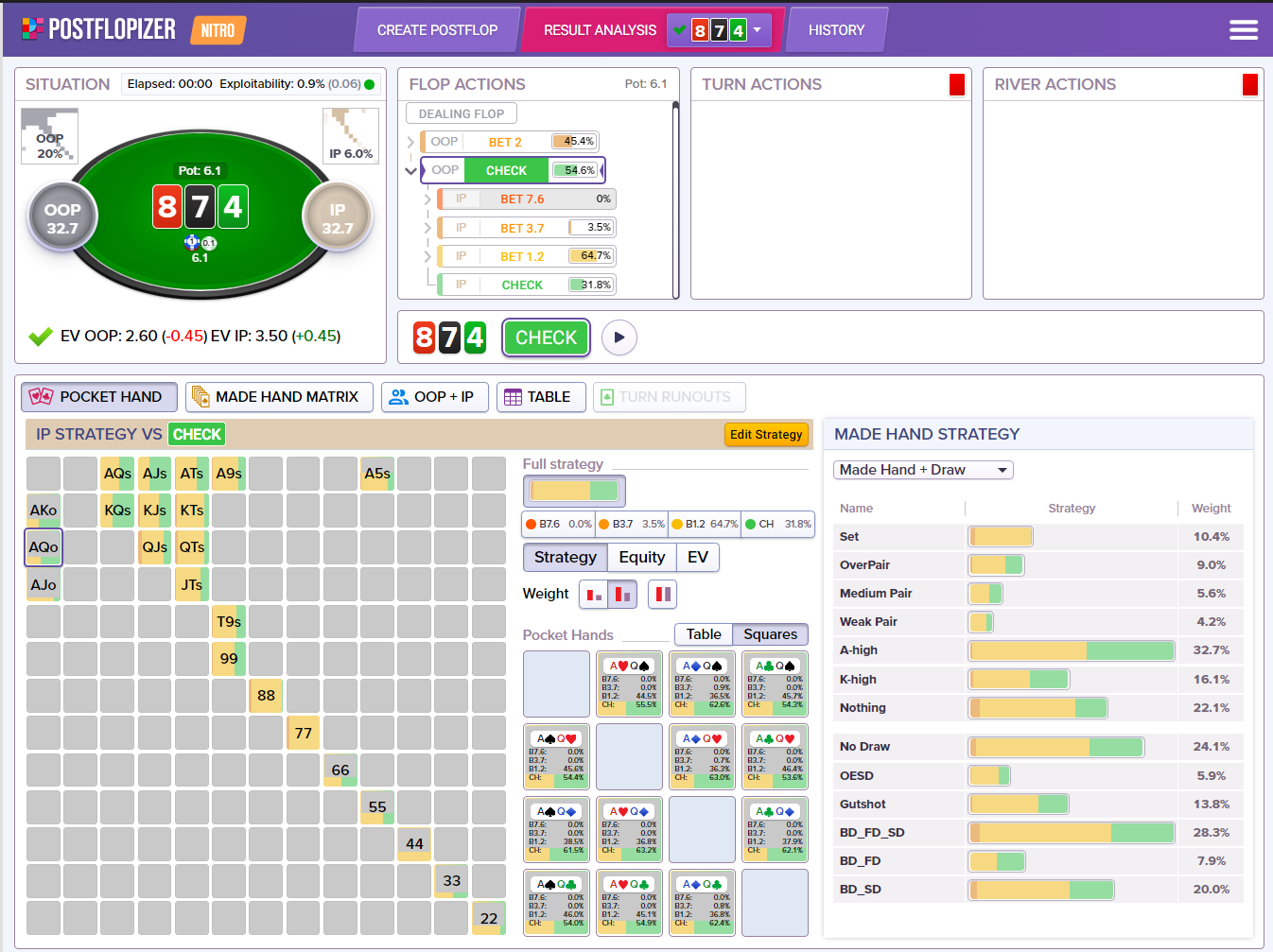

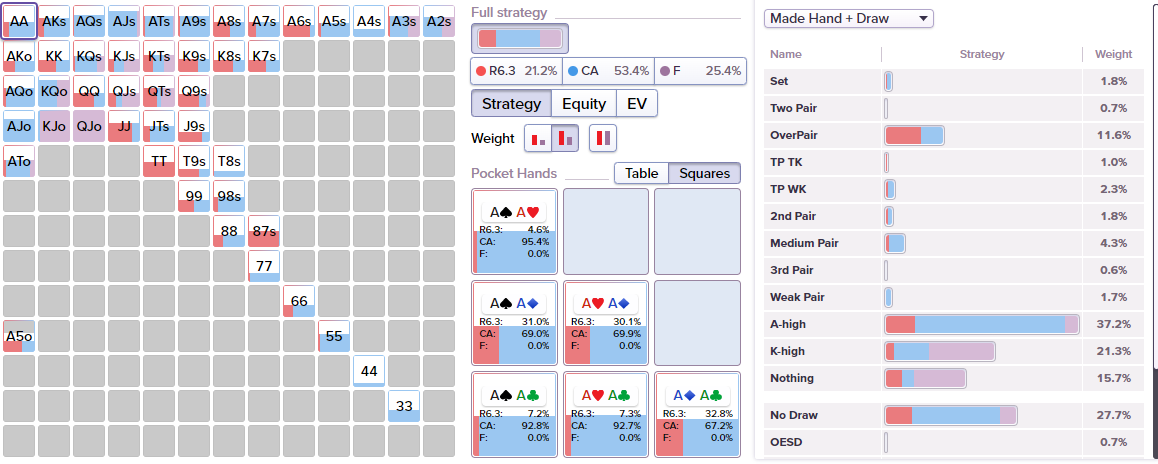

Let’s say in real life, you were the IP player and you had A♣Q♦. Your opponent checked to you on the flop and you checked back. This is what Postflopizer does in that spot:

As you can see, your hand checks back most of the time. But what does the range do? Well, most of the time it bets.

Ask yourself why your range does this.

One answer might be that with relatively close ranges, a check from OOP is a sign of weakness that can be capitalised on. This is a flop that they are unlikely to have hit and they will have to fold a lot. Add to that the fact that you have position, meaning you can put them in a tough spot on the turn and/or river if they continue.

Your range wants to bet, and this is the important takeaway here, rather than what your hand did. So while you were right to check back, be prepared to bet a lot when a similar scenario comes up.

What are the outlier hands?

We have looked at what the range wants to do, now is the time to look at individual hands. This question is a really important one. In fact, this is perhaps the question where you can learn the most from solvers. Ask yourself which hands deviate from the range strategy, and why?

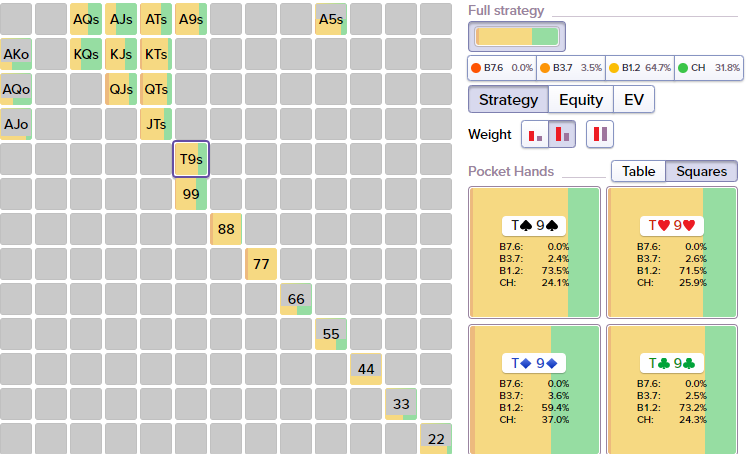

Looking at the range again:

The range mixes and mostly bets. A hand like ATs closely mirrors what the range wants to do, betting around 70% of the time and checking the rest.

The outlier hands here are 88, 77 and 44, all of which bet 100% of the time. This is for obvious reasons, they are Sets and want to get value.

AKo, AQo and KQs are also outliers in that they bet rarely. This is more of a head-scratcher. One interpretation might be that they are likely ahead of the checking range, but if they bet, they will fold out all the hands they beat and only get called by better hands.

We can test this assumption by looking at the response to the small bet:

When you bet, the hands that fold are all Kx and the worst Ax. Nothing better folds, so betting with AQ+ here doesn’t work as a bluff. Some worse hands call, but they are all hands that have some backdoor equity. KTs and KJs for example can hit runner-runner straights as well as spiking a pair.

When IP bets, OOP raises a lot of worse hands as bluffs. They raise KQs-KJs as well as worse Ax quite often. We would hate to have to fold AQ to a bluffing KQs.

So the reason we check back with AKo, AQo and KQs most of the time is because they don’t make better hands fold, few worse hands call, but crucially they make worse hands bluff raise, forcing us to fold.

As you can see, when you ask yourself ‘What are the outlier hands, and why?’ you can arrive at some very useful lessons learned. Get into the habit of doing it.

What are the bluffs that go with my value?

A well-constructed GTO range will have the right proportion of bluffs and value. Value bet too much and your bluffs won’t get folds. Don’t bluff enough and your value bets won’t get paid.

A very useful exercise is to look at which hands the solver chooses to bluff, to go along with the value bets. Don’t get too bogged down in the frequencies of bluffs-to-value just yet, let’s just look at the hands chosen to bluff.

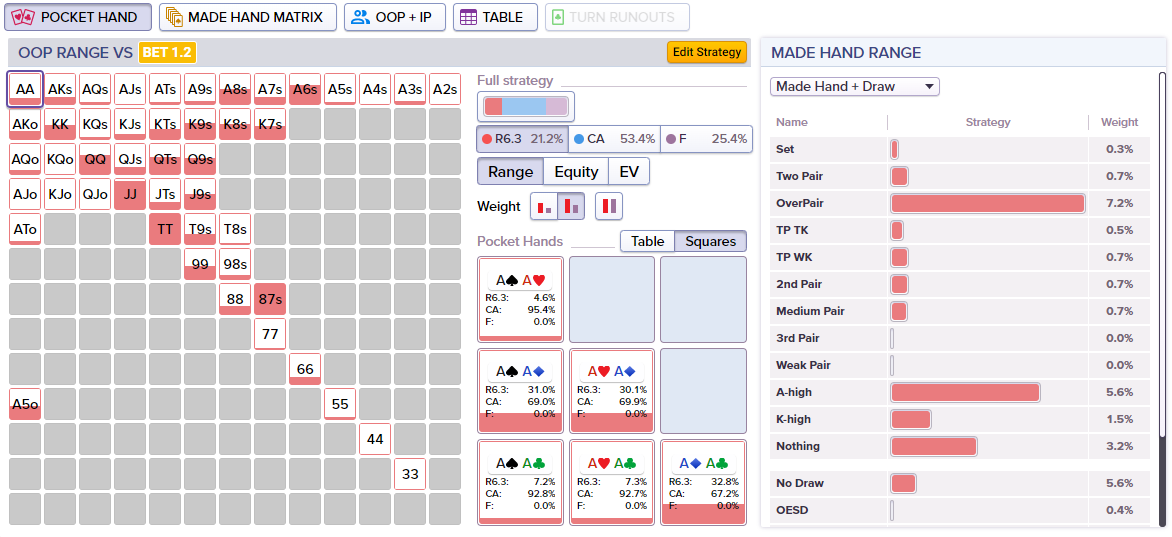

Going back to the OOP response to a small bet, these are the check/raises:

The Sets raise about half the time and call about half the time. Two pair always raises and overpairs raise most of the time. The one pair hands mix their actions a lot. This probably all makes sense.

What are the bluffs here?

Ace high bluffs a lot. It can spike an Ace if called and will likely be ahead. However, the most common Ace bluff is A6s and A5o, because these two hands have gutshots to go with their overcard. AK bluffs a lot because the K kicker is also useful.

Kx raises, with KJs bluffing more than KQs, KTs bluffing more than KJs, and K9s bluffing more than KTs. This is mainly because the lower the kicker, the more likely it is they can hit a runner-runner straight.

The best draw is T9s because it has an open-ended straight draw, but it only bluffs half the time. A lot of players would assume we should always bluff our best draw, but from a GTO perspective, we would hate to have to fold it to a raise. We also want to have ‘runout coverage’ ie. we want it to be possible to have turned a straight when we call and also when we raise the flop. More on that in a moment.

Asking yourself which bluffs go along with the value is a very useful exercise and will help you decide on your bluffs in the moment when you are at the table.

A Postflopizer tool not to be ignored is the ‘Turn Runouts’ and ‘River Runouts’ buttons. Get into the habit of looking at this before you put out the actual Turn or River card that occurred in-game.

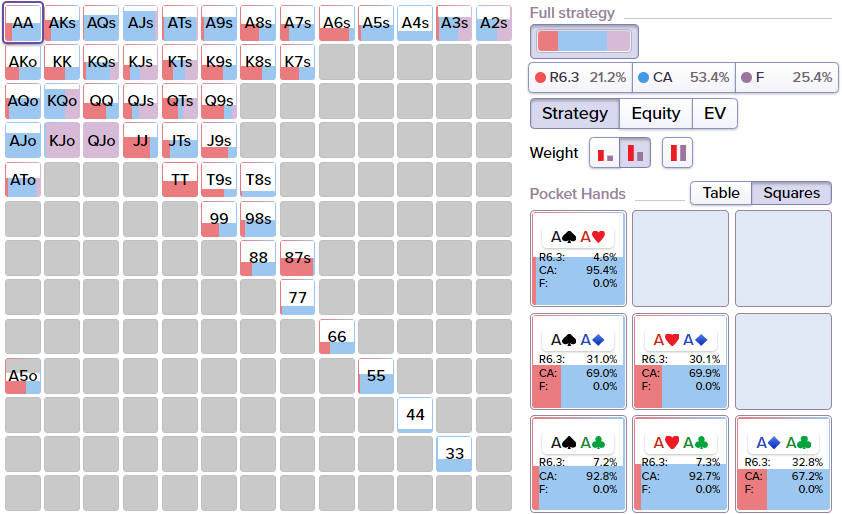

You get a wealth of information for every possible Turn/River card. You get the equity, EV and next actions for each. Let’s assume IP called the check/raise. These are the stats and next actions for OOP:

Here we can see that the best Turn cards for OOP are 8s and 7s, which are all worth 52.9% equity or better and would commonly lead OOP to bet (the bar underneath the card previews the betting and checking frequencies).

The worst cards for OOP are Jacks, which are worth 44.7% equity or worse (meaning they are worth 54.3% equity or better for IP) and would always lead OOP to check.

This is because OOP had 88, 77 and 87 in their check/raising range. They also had all the overpairs that will typically be strong on a paired board, because a paired turn card reduces the chance of a straight happening and increases their chance of getting a full house by the river.

The Jack is better for IP, as we mentioned from the outset they have a higher proportion of Broadway hands like KJ and QJ. T9s for a straight is also a higher proportion of their range than it is for OOP. Tx and 9x are also a higher proportion of their range, giving them a gutshot they can bluff with.

Looking at the Turn and River Runouts helps you understand the shape of each range better and crucially is very useful for when you play. Being able to tell yourself the good and bad Turn/River cards in-game before they are dealt will help you adjust in the moment at the tables, rather than being flummoxed about what to do when a surprise turn card hits.

Look at the EV of key hands/actions

One final habit to implement is to pay attention to the EV (Expected Value) of the trickier decisions. Let’s go back to the flop when OOP was facing a bet and pondering whether to Check/Raise.

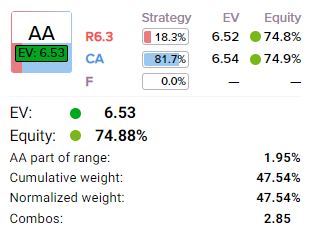

If you select EV and then hover over each hand, it will show the profitability of each action. For example AA:

AA makes us 6.52BBs as a raise and 6.54BBs as a call. It makes slightly more as a call than a raise, perhaps because it crushes a lot of IP’s value and we would expect IP to bet a lot on the turn. However, the EV is close between the two which is why it mixes.

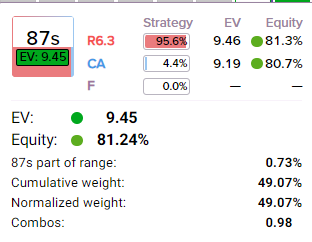

Let’s look at 87s:

87s, which is top two pair, makes 9.46BBs on average as a raise and 9.19BBs as a call. It is clearly more profitable as a raise, which anyone who has played poker will understand, because top two pair shrinks in value by the river, so better to get the money in now. This is why 87s is a pure raise. The 0.27BBs difference might not seem much, but over the long-term calling, instead of raising, with it is a 27BB/100 error, which is a huge mistake.

Don’t get bogged down in looking at the EV of every hand and every line, but certainly do it for the big hands, the close hands and the tricky hands. What may seem like a small difference between two strategies can be an overwhelming difference over the long term.

Conclusion

There are so many more important questions to ask during a hand review, but what we have just looked at will really bring you up to speed with what a powerful GTO Solver tool like Postflopizer is capable of. We have only just scratched the surface of what else you can learn from it, so once you have these basics down, follow your curiosity.